Terraformer For Dummies

Arihant Gadgade

Terraformer Research Project Directory

Date Published: 6/26/2025

Contents

- 1. Introduction: Overview of what the Terraformer is and why it's necessary

-

2. Energy: Contextualizing Terraformer in terms of energy supplies and sources

- 2.1. Terraformer Unit Energies: Giving an idea of the energy scale of a single Terraformer unit

- 2.2. Global Energy Primer: Giving an idea of the yearly energy consumption of the world

-

3. Terrafomer and Energy Economics: Understanding the economics allowing Terrafomer to be profitable

- 3.1. Energy Economics: Understanding the cost trends for energy sources, and why this bodes well for Terraformer

- 3.2. Terraformer Module Economics: Understanding the economics for a single Terraformer unit

-

4. How Terraformer Actually Works: Accessible explanation of the Terraformer

- 4.1. Overview: Gives an overview of the Terraformer, it's subunits, and the science and processes

- 4.2. Production: States the goal of mass manufacturing Terraformers

1. Introduction 🔝

This is meant as a fairly simplistic introduction to the Terraformer. I'm writing this in an effort to learn about the technology for myself, and

explaining it will hopefully provide value to those who read this too.

Trees can be thought of as machines that consume solar energy and CO2 and produce burnable fuel. The Terraformer has a similar process,

except it is more efficient (if interested, check out "10: Realignment of Insecure Energy Supply Chain" in

Terraformer Environmental Calculus).

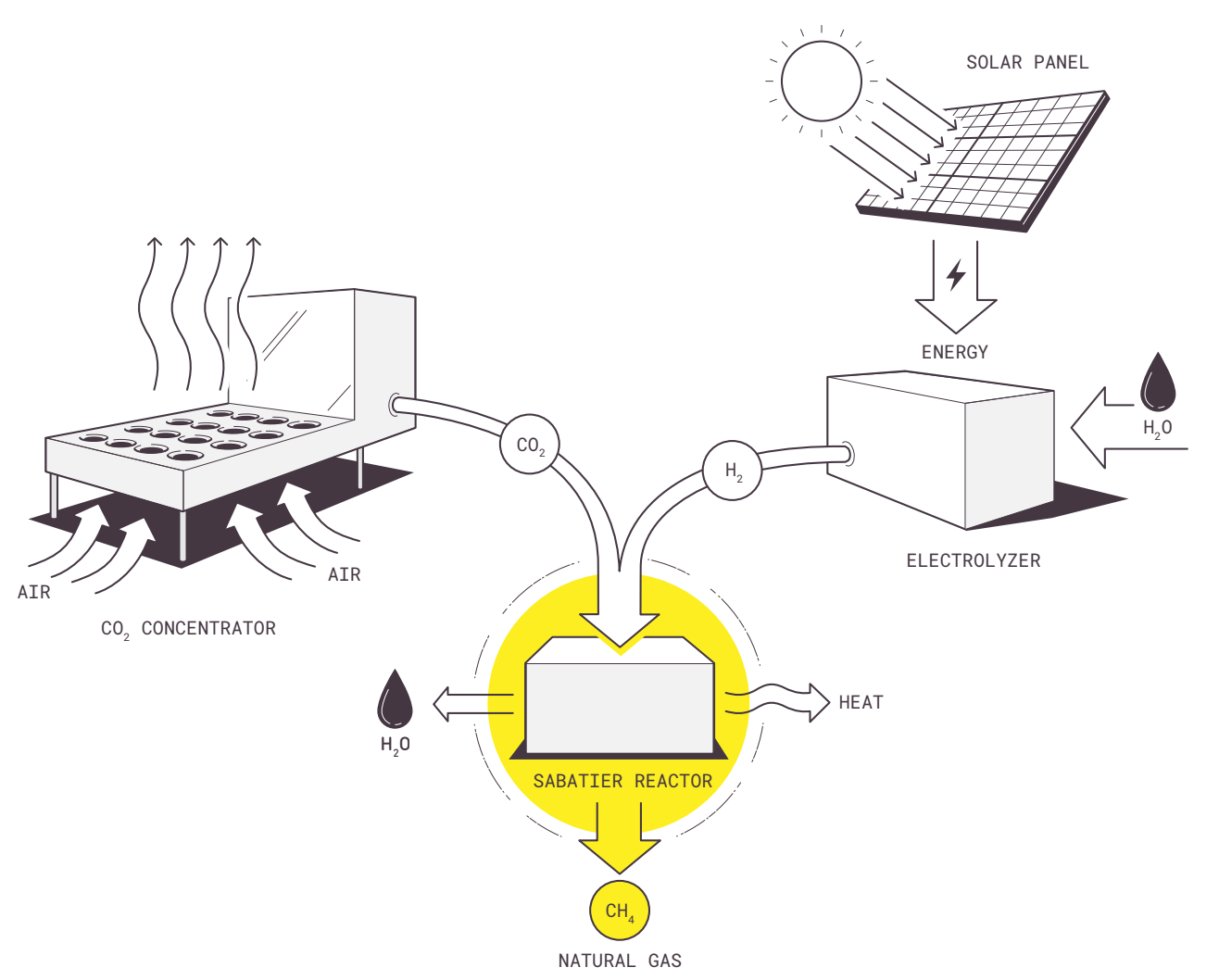

Simply put: the Terraformer is a solar powered machine that is fed in water and captures C02 from the air, then using the H2

from the H2O and captured CO2 converts this to natural gas (methane). And like using trees for fuel it is carbon neutral.

[Picture from Terraform Industries Whitepaper 2.0]

The reason Terraform Industries believes this is a worthwhile machine to create is that: we need hydrocarbons to power our world, we need carbon neutrality

to combat climate change, and our current fossil fuel supply will eventually run out.

Structure of this Article:

The reason that I wrote about the energy supply and economics first is to motivate the problem.

Then, you can see why Terraformer is a necessary solution, and the science of how it works will stick better. At least

for me, having an updated world model helped with contextualizing the Terraformer into that model, so I wrote it the way

that makes sense to me.

2. Energy 🔝

2.1. Terraformer Unit Energies 🔝

There are two energy amounts to understand to get a scale of the

energy consumption of a

Terraformer Mark One

unit: electrical energy from solar to power the unit

and the thermal energy released from the synthesized natural gas.

I will compute these quantities and then I'll show them in terms

of a familiar energy unit: the amount of energy it takes to charge an

iPhone, specifically the iPhone 14 Pro. Talking in terms of a Watt-second (Ws)

or Watt-hour (Wh) was a bit abstract for me, and I felt like talking in terms

of the energy to fully charge an iPhone 14 Pro battery (iBat) was a bit more intuitive for me.

Then I'll show you the equivalent natural gas output in terms of a Toyota Camry gas tank to get a scale of

the synthetic gas production.

Prereqs to follow the calculations are only some basic physics concepts:

Power = Energy / time, some dimensional analysis skills, etc.

The Terraformer Mark One in Wh:

Unit's power consumption:

Energy to power the unit for one hour: 1MWh [One Terrafomer unit is designed to work with a 1MW solar array to get its electrical energy]

Unit's synthetic natural gas output:

Synthetic natural gas output in one hour: 1000ft3

So now we'll want to convert the amount of natural gas we have to thermal energy,

as this is the form of energy we can get from the chemical bonds in the gas through

combustion. And thus thermal energy is useful b/c this is the intermediate form we convert

to other useful forms, or keep as heating.

Synthetic natural gas conversion to thermal energy:

1000ft3 = 1038000 Btu [source]

[British thermal units (Btu) were created as a standardized measure of the thermal enegy that can be extracted from a fuel source through combustion]

1038000 Btu = 304220 Wh [1 Wh = 3.412142 Btu]

Thus, we see the unit's thermal energy output:

Thermal energy in the form of synthetic natural gas outputted in one hour: .304MWh

So, we can calculate efficiency:

(Thermal energy output)/(Electric energy input) = .304MWh/1MWh = .304

Therefore, we have about a 30% efficiency. I'll explain in section 2.2 why we are fine with this.

The Terraformer Mark One in iBat:

Using:

Electric energy input: 1MWh

Thermal energy output: .304MWh

Setting up the metric that fully charging one iPhone 14 Pro battery is one iBat:

1 iBat = 12.38Wh [source]

Therefore we can see input/output energy in terms of iBats:

Electric energy input: 80775iBat

Thermal energy output: 24556iBat

So we see that the energy required to run the Terraformer for an hour is equivalent to fully charging

~80000 iPhone 14 Pro batteries. And the thermal energy output in the form of synthetic natural gas we get

from an hour of the Terraformer is equivalent to fully charging ~25000 iPhone 14 Pro batteries.

The Terraformer Mark One Compared to Car Gas Tanks:

Using a Toyota Camry as a standard size gas tank:

Toyota Camry gas tank = 15.8gal of gasoline [source]

The thermal energy of this gas tank:

15.8gal * 125,000 Btu/gallon = 1.975million Btu [source]

Thus we can see how many gas tanks are filled per hour by the Terraformer:

1038000 Btu / 1975000 Btu = .52 [using our earlier result]

Thus we see that the Terraformer produces about half a Camry gas tank per hour worth of hydrocarbons.

Let's see what this is per year:

.52gastank/hr * 2190hr/yr = 1139gastank/yr [Terraformer will run 2190hrs per year

(1/4 the year or 6hours a day) because solar power is effectively available only 1/4th the day, as

during the night there is no sunlight and during the day sunlight intensity varies]

So we see that one Terraformer produces about 1139 Camry gas tanks per year worth of hydrocarbons.

So now we have an idea of the efficiency, some intuition for the energy, and some intuition for the gas production of the Terraformer.

2.2. Global Energy Primer 🔝

The world needs energy to run, but where are we getting this energy from?

Classifying Energy Sources:

- Non-renewable sources

- Fossil fuels

- Coal

- Natural gas

- Oil

- Nuclear

- Renewable sources

- Solar

- Wind

- Hydropower

- etc.

Non-renewable energy sources are conversions from stored mass to usable energy,

via chemical bonds (combustion) or mass defects (nuclear).

Renewables can be thought of as harvesting external energy flows (e.g. sunlight or wind).

While most renewable energy storage focuses on batteries, Terraform takes a different approach:

storing solar energy as synthetic hydrocarbons. [Fun note: On a universal timescale, no energy is renewable,

according to our understanding of entropy.]

Hydrocarbons are substances with hydrogen-carbon bonds. We refer to them a lot because they

store a lot of energy in their chemical bonds, and we like releasing this energy in the form of

heat. Example of hydrocarbons are fossil fuels: coal, natural gas, oil. Hydrocarbons are incredibly

crucial to our energy supply, as I'll explain now.

Ok, so you might ask: [question from "The Terraformer Mark One in Wh" section] why do we turn the already

useful form of electrical energy from solar into another form of energy (thermal energy from hydrocarbons),

especially if we are less efficient in doing so? Well the answer is essentially because energy form matters.

With hydrocarbons we can use it with the current infrastructure (automotives, heating, industrial, etc) that is

already built out so that we can decarbonize them, hydrocarbons are a direct store of energy (whereas solar needs

batteries), etc. So, Terraform Industries is essentially making the argument that even if we switch out fossil fuels

fully with solar power, there is still usefulness in hydrocarbons, so much so that being only 30% efficient with solar

energy is still worthwhile.

Now that we have an overview of the classification of energy, let's begin to look at how

we use them.

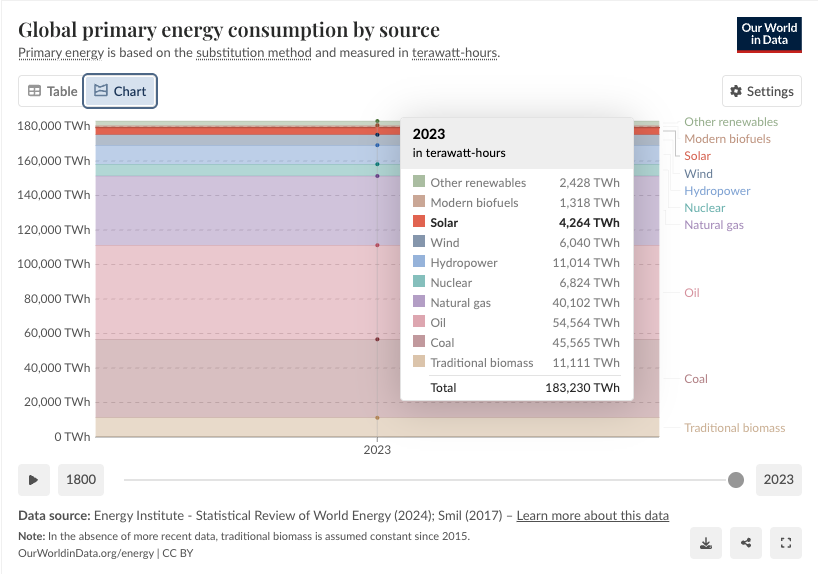

[Chart from Our World in Data]

So from this chart, we can see the total energy consumption of the world in 2023,

as well as the percentage each energy source contributed.

Total primary energy consumption in 2023: 183,230TWh

As a fun exercise lets conceptualize this in terms of iBats:

Total primary energy consumption in 2023: 183,230TWh / 12.38Wh = 1.48*1016iBats

Continuing on in terms of global population:

Total primary energy consumption in 2023 per person: 1.48*1016iBats / 8billion = 1.85 million iBats

Therefore the total primary energy consumption in 2023 per person would be as if each person was responsible

for fully charging approximately 1.85 million iPhone 14 Pros in a year.

Now let's look at the energy sources we are interested in:

Total solar energy consumption in 2023: 4,264TWh

Total fossil fuels energy consumption in 2023: 140,231TWh

Thus we see:

Solar percentage of total energy consumption in 2023: 2.3%

Fossil fuels percentage of total energy consumption in 2023: 76.5%

So now we can use the fact that the Terraformer will run 2190hrs per year (1/4 the year or 6hours a day)

to then calculate how many Terraformers we would need to replace fossil fuels in 2023.

Thermal energy output per year (in the form of synthetic gas): .304MWh * 2190 = 666MWh

Number of Terraformers needed to replace fossil fuels in 2023: 140,231TWh / 666MWh = 210 million

Therefore, we see that we would need 210 million Terraformers to replace the fossil fuel industry in 2023.

So let's see how much solar generated energy we would need to fuel these 210 million Terraformers for a year:

210 million Terraformers * 1MWh * 2190hours = 461,286TWh

This is a massive amount, it's 2.5x the total energy consumption in 2023 and 108x the total solar energy production in 2023.

It's time to build!

3. Terrafomer and Energy Economics 🔝

We now have a scale of the energies, let's attach some dollar values.

Ok, let's start getting a sense of the dollar value.

Home Energy Prices:

I think it's useful to mention some residential electricity costs to have some reference.

I live in Georgia, so I'll use the average costs for electricity for a home here:

Average electric rate: $0.15/kWh [source]

Average yearly electric bill: $2,544/yr

Average yearly electric energy usage: 17000kWh

Using the iPhone battery analogy again:

Cost to fully charge an iPhone 14 Pro: 12.38Wh * $0.15/kWh = $.002

So, it only costs a fifth of a penny to fully charge an iPhone! You can check out the main

costs/usage of home electricity here.

And for fun:

Yearly home energy usage in iPhone 14 Pro battery units: 1.37million iBats

3.1. Energy Economics 🔝

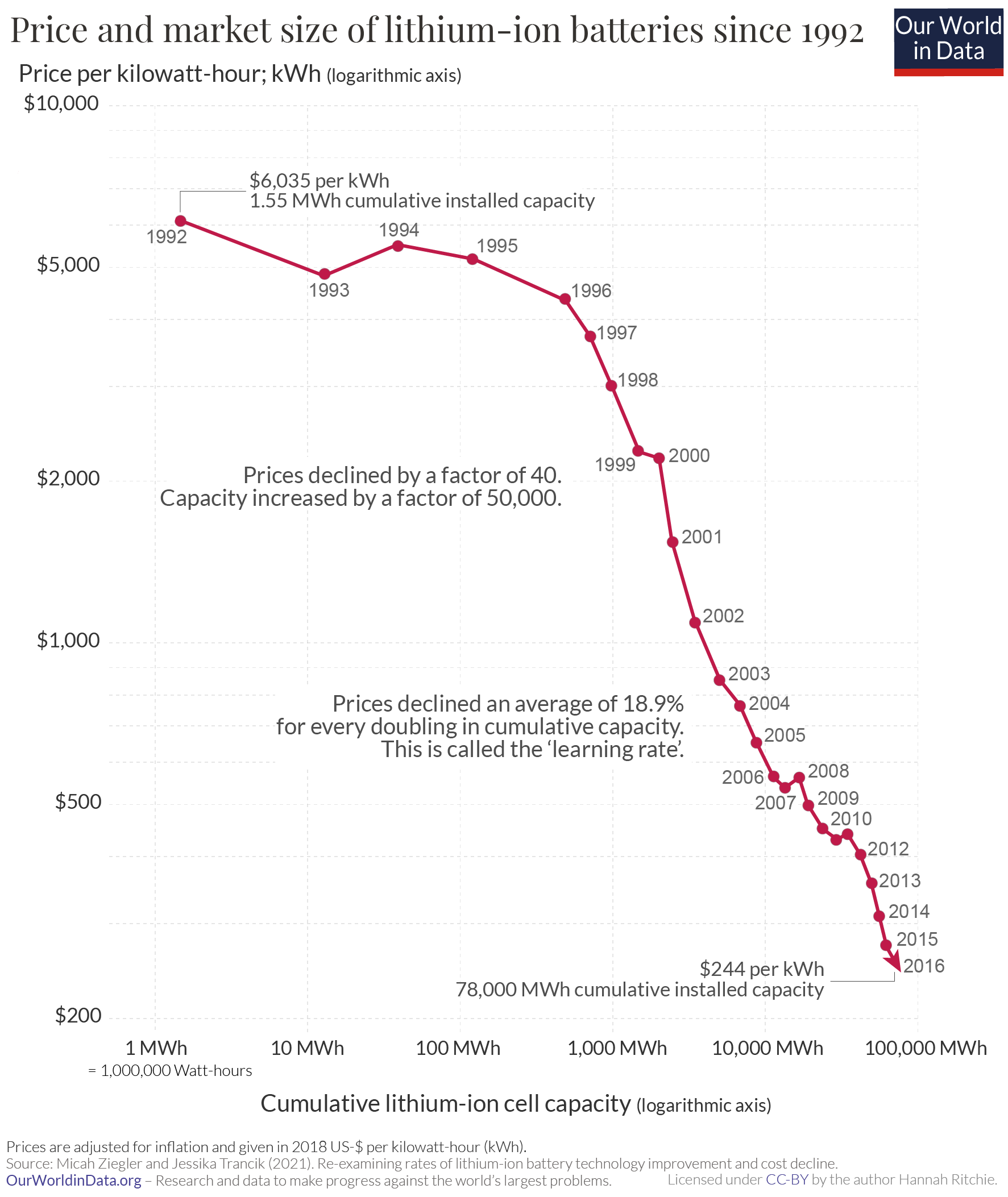

Now we have some idea that energy is important and our current energy is mainly coming from fossil fuels. But, we want our future energy to mainly come from solar instead of fossil fuels. So, if we want this to happen it needs to be economically feasible. If fossil fuels are still cheaper than solar, there will not be enough of an incentive to change. Luckily for the world and Terraform Industries the data shows that not only will solar be cheaper, it will be radically cheaper, so much so that we can use the energy inefficient (~30% as calculated earlier) Terraformer to replace our current fossil fuel industry, as the Terrafomer synthesized hydrocarbons will be cheaper than fossil fuels. Batteries are also getting cheaper, which is important because we will need this to have an electric grid that can sustain solar's intermittency or else solar won't actually be cheaper than fossil fuels, as the grid won't handle our current usage (I'll explain this more later).

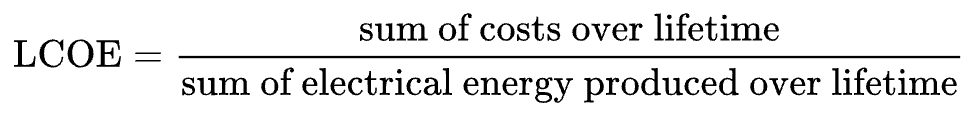

Ok, let's look at current energy economic trends. To do this we need a

standardized way to compare costs of different energy sources. Thus we use the

levelized cost of energy (LCOE).

LCOE:

The LCOE of an energy source is defined as the sum of lifetime costs (cost to build and maintain the plants) divided by the

sum of lifetime electrical energy produced. It can be thought of as the average cost

per unit energy (e.g. units of $/kWh).

[Picture from Wikipedia]

Illustrative example of using LCOE: if an LCOE for energy A is $5/kWh and an LCOE for energy B is $3/kWh,

then energy A is a more expensive energy source than energy B, because we are spending more per kwh for A than B.

Thus we are always looking for the lowest LCOE.

Note: LCOE is dependent on the scale of the energy you are producing, where it is typically cheaper for a larger power plant.

So generally you are going to want to have a bigger plant to have a reduced LCOE. Economies of scale basically dictate that bigger

means cheaper per unit. But we just keep this in mind and will compare a 10MW coal plant to a 10MW solar plant, or a 10kW coal plant

to a 10kW solar plant, etc.

So, reiterating, the reason we use LCOE instead of just cost per unit energy is to factor in the cost

required to build and maintain the physical infrastructure that generates the power.

Energy Trends:

Essentially:

- currently, electricity from solar is cheaper than from fossil fuels

- the cost at which solar is falling is much more drastic than fossil fuels,

which are comparably flat.

The data for this is from Our World in Data, and you can read more about this there

(in there, they talk more about learning curves, which are the explanatory model that

predicts these cost changes, which I will mention soon).

Here we can see the trend illustrated:

.png)

From this graph we see:

Cost of electricity from Solar PV: $60/MWh

Cost of electricity from Coal: $115/MWh

Showing that solar is less expensive per MWh than coal.

For reference, here's the residential prices from earlier to compare:

Average electric rate: $0.15/kWh = $150/MWh

To understand these trends, its necessary to understand the learning curve effect.

The learning curve effect basically states that as people or organizations repeat a task,

they learn how to do it better, faster, and cheaper. This is happening in solar and batteries,

but not in fossil fuels. This is the fundamental reason why Terraform Industries is going

to succeed.

Ok so we see that solar is cheaper, so we should build that out, but building takes time and money, so we can't overnight ditch fossil fuels.

Are there any other impediments to a fully solar energy grid? Yes, there are and it has to do with

the intermittency of solar. Solar is too irregular a power supply, but we need our grid to be more

stable, so the solution is batteries (which is why batteries following learning curves is necessary), which we will

talk about in the next section.

Battery Trends:

To understand why we need batteries, we need to understand how the electric grid is designed now.

Fossil fuel plants already have stored energy, the fossil fuels themselves, thus they do not

need much more additional storage, they can just burn to meet demand. Solar does not have that luxury.

There is no way to just store sunlight in a bottle, we can only transfer that energy to a battery in

order to store it. Since the grid is built for fossil fuel plants, we use the luxury of not needing

lots of battery capacity. But if we want to transition to solar, we can't afford the luxury of not needing

batteries, because when we want more energy than solar is producing we have no store to pull from without batteries.

This cost of batteries was/is a barrier to upgrading the grid to solar (and other renewables).

But, the falling prices of batteries allows this to be economically feasible, where the combination

of solar+batteries for electricity will be cheaper than fossil fuel electricity.

Here we can see the trends of falling battery prices:

Summarizing:

So essentially we see that Terraform Industries is making a bet

on our energy supply transitioning to solar energy + batteries. And the trends seem to indicate that

this will be profitable.

3.2. Terraformer Module Economics 🔝

Ok so we can see the Terraformer unit economics from Terraform Industries Whitepaper 2.0:

"Each 1 MW module produces around 6.5 kcf (thousand cubic feet) of natural gas per day (assuming 25% utilization or 6 hours of sun per day), so at a gas price of $10/kcf, each module produces $65/day of revenue, or $24,500/year."

"With 5 year module lifetimes, each module will generate $119,000 in revenue ($656,000 including IRA incentives) against capex of $30,000 for the module and $16,000 for 1/6 of the 1 MW solar farm. Even including interest and maintenance costs, this margin is significantly healthier than existing fossil fuel production, and Terraform is well positioned to capture value from the raw commodity stream as well as module manufacturing."

Financial Primer:

- Total Cost: Capex + Opex

- CapEx vs OpEx: Capex is capital expenditures, it refers to cost of

buying longer term assets. Opex is operating expenditures, it refers

to day-to-day costs with maintaing assets.

- Revenue: How much income is generated from sales.

- Net Profit: Revenue - Total Costs

Profit Breakdown of One Module using the Whitepaper:

Lifetime: 5yrs

Capex:

Cost to build one module: $30,000

Cost of 1/6th of 1MW Solar panel: $16,000 [Here I'm assuming

they are using the lifetime of 1MW solar panel at 30yrs, and splitting that

among 6 five-yr Terraformers, thus the total cost of a 1MW solar array is $96,000]

Total Capex for a 5yr unit: $30,000 + $16,000 = $48,000

Opex:

Total Opex for a 5yr unit: not specified, assumed to be not large enough to disrupt price calculations

Revenue:

Gas production per day: 6.5 kcf

Price of gas produced per day: 6.5 kcf * $10/kcf = $65

Price of gas over 5 years: $65/day * 365day/yr * 5yr = $118,625 [~$190,000]

Net Profit:

Net Profit = Revenue - Total Costs : $190,000 - ($48,000 + opex) = $71000 - opex

Note: I've ignored subsidies, as they believe their financials are solid even without them, but with the subsidies, they are in a much healthier position.

They believe this positions them well financially to capture the hydrocarbons market.

Check out the Whitepaper for more in depth economics and the Total Addressable Market (TAM).

4. How Terraformer Actually Works 🔝

Now that we've contextualized how Terraformer will fit in the global energy supply and economy, let's get on to explaining how a Terraformer works. I will first give a high level overview, such that one can have an idea of how the module works, then I will increase the depth of the explanations.

4.1. Overview 🔝

Terraformer Overview:

The Terraformer is a machine that capture carbon dioxide and produces methane.

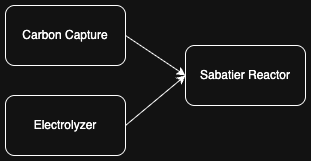

The Terraformer is comprised of 3 subunits:

1. Direct Air Carbon Capture system

2. Electrolyzer

3. Methanation

The carbon capture unit is what's responsible for combatting climate change

by removing CO2 from the atmosphere.

The electrolyzer creates the hydrogen gas from water necessary for the "hydro"

in hydrocarbons.

Methanation is the money maker, this is where we take CO2 and H2

and turn them into our useful CH4 product. Thus, allowing us to successfully

monetize carbon capture, not to mention this will be cheaper than current methods of

methane production.

Engineering of the Subunits:

The carbon capture unit works by pulling in air from the atmosphere, then humidifying

the air, running the air through calcium hydroxide (slaked lime) such that it turns into calcium carbonate (limestone), and

this is where the CO2 is being sequestered.

This calcium carbonate is then heated up in a kiln so the CO2 gas can then be

extracted and sent to the Sabatier reactor. These lime forms are cycled until used up.

The carbon capture unit works by pulling in air from the atmosphere, then humidifying

the air, running the air through calcium hydroxide (slaked lime) such that it turns into calcium carbonate (limestone), and

this is where the CO2 is being sequestered.

This calcium carbonate is then heated up in a kiln so the CO2 gas can then be

extracted and sent to the Sabatier reactor. These lime forms are cycled until used up.

The electrolyzer works based on the process of water electrolysis: electricity is used to separate

water into hydrogen and oxygen gas. The oxygen gas is vented off, while the hydrogen gas is sent to

the Sabatier reactor.

The Sabatier reactor takes the fed in carbon dioxide and hydrogen gas, then combines them in appropriate ratios,

feeds them into the reactor chamber where they are heated, pressurized, and subjected to a nickel catalyst. This

allows the named Sabatier rxn to occur. The effluent gas is then cooled, and the methane is properly stored.

Chemical Rxns:

Calcium Looping in the Carbon Capture System:

Slaking: CaO(s) + H2O(g) -> Ca(OH)2(s) ΔH = -110.2 kJ/mol

Carbonation: Ca(OH)2(s) + CO2(g) -> CaCO3(s) + H2O(g) ΔH = -68.3 kJ/mol

Calcination: CaCO3(s) -> CaO(s) + CO2(g) ΔH = +178.5 kJ/mol

Electrolysis:

2H2O(l) -> 2H2(g) + O2(g)

Sabatier Reaction:

CO2 + H2 -> CH4 + 2H2O ΔH=-165 kJ/mol

Terraformer Research Project Writeup:

You can read more on the Terraformer here:

TRPW

4.2. Production 🔝

Mass manufacturing is key. The mechanisms of the subunits were chosen so that the Terraformer can be mass produced cheaply, and take advantage of cheap solar power. Capital efficiency > electrical efficiency.